The aim of this paper is to explore the common ground between the conceptions of space prevalent in the 18th century and the development of a specific type of portable technology: board games. Initially, this new medium of entertainment was designed for middle-class, young adults in 18th century British society. The purpose of these games was to encourage these young adults to conceive of themselves as citizens in the midst of the transformations taking place at the time in industrial England. As such, these games were closely linked to the simultaneously emerging notion of domesticity, i.e. the increasing concern for the nature of the day to day lives of families in their homes. A major reason for this concern had to do with the fact that the home was seen as one of the main spaces wherein the education of these young adults—who were to become both the citizens and workforce constituting society—would take place.

This conceptual linking of the domestic education of young adults to the new medium of board games was in part driven by new concern for the scientific representation and technological development of the modern world.

Thus, in order to encourage young adults to take an interest in the modernizing capacities of both the natural sciences and industrial technology, the educational dimension of many of these domestic board games was often tied to the representational capacities of cartography.

Alongside this desire to produce future generations of scientifically and globally-minded adults, the 18th century also produced a rich body of literature on a variety of new scientific and technological artifacts developed outside of the home. This literature was then brought into the home with the ultimate goal being the construction of a new type of subject: the individual who participates in the collective endeavor to modernize the world with the conveniences of science, engineering and technology. This paper suggests that these three histories are connected not only spatio-temporally but also that these three social currents are conceptually and ideologically interrelated insofar as the emergence of board games functioned as an instrument for the construction of this new form of subjectivity, which was based on emerging transformations in the types of knowledge, education, and citizenship required for this new collective project of modernizing the world.

Fig. 1. A New and Accurate Map of Scotland from the latest Surveys.

Fig. 2. A new geographical game exhibiting a complete tour through Scotland and the Western Isles. London, 1792, Published by J. Wallis and E. Newbery. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 3. Bowles’s geographical game of Europe. [London], ca. 1800, Published by Bowles and Carver, Designed by Dr. Nugent. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Part 1: The spatial imaginary of the 18th century and the historical emergence of domesticity

Fig. 2. A new geographical game exhibiting a complete tour through Scotland and the Western Isles. London, 1792, Published by J. Wallis and E. Newbery. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 3. Bowles’s geographical game of Europe. [London], ca. 1800, Published by Bowles and Carver, Designed by Dr. Nugent. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Part 1: The spatial imaginary of the 18th century and the historical emergence of domesticity

The first part of this paper deals with the ways that the shifts in everyday life that arose out of the transformations in the types of employment as well as the new arrangements of domestic labor during the Industrial Revolution resulted in a further transformation of the way space itself was conceptualized in the 18th century. The development of these new manufacturing processes in Europe and the U.S. also entailed a restructuring of the family unit, a reorganization of the household economy, and a general shift in daily routines.

The historical emergence of domesticity also brought about new forms of specifically domestically-oriented entertainment aiming to bring together different scales of physical space—e.g., the nation, the continent, the world—into the context of the home. This coincidence of scales allowed for an understanding by these new “middle-class citizens” as agents upon the world stage. At the same time, children and women would become the fundamental determinants of this new form of everyday life that discharged children from the duties of craft apprenticeship, since manufacturing industries began to grow and women began to contribute to a family’s income.

Part 2: Connections to Cartography

The moment when the first board games were published coincides with important transformations in the English Empire related both to infrastructural as well as social change. In addition to the boom in economic growth in England from 1760 to 1840, which completely transformed English society at the time, the relation between Great Britain and its colonies also changed dramatically.

This new form of governmental dynamics is essential, I claim, in order to understand the role of board games in shaping British society and its colonies (both former and otherwise) primarily for the ways boardgames expressed the conceptions of measuring and representing geographic spaces, which were part of these new ways of governing populations.

The role of maps in facilitating an understanding of the world without the necessity of travelling became popular in England during the end of the 18th century, which, at the time, would come to play a major role in the development of a new genre of the board game. In these games, players took on the role of “tourists” or “travelers” (with the player’s pieces being labeled “servants”), and were designed around the idea of encountering at each turn what actual tourists at the time might have encountered. The instructions of the game, printed on the left and the right side of the map refer to the pyramids, used as tokens as “the travelers supposed to make the tour.” Another board game, “Bowles’s geographical game of Europe” was published by Bowles and Carver (ca. 1800) in London and was designed by Dr. Nugent, who wrote one of the most trusted travel guides of the 18th century. So in addition to teaching geography and history through play, the purpose of these kinds of games was to enhance the spirit of inquiry and the adventurous nature of children of the middle class. By using the actual maps and guides that travelers used in their tours, publishers were trying to make the connection between the practice of an adult passing through space and a child’s imagined tour clearer.

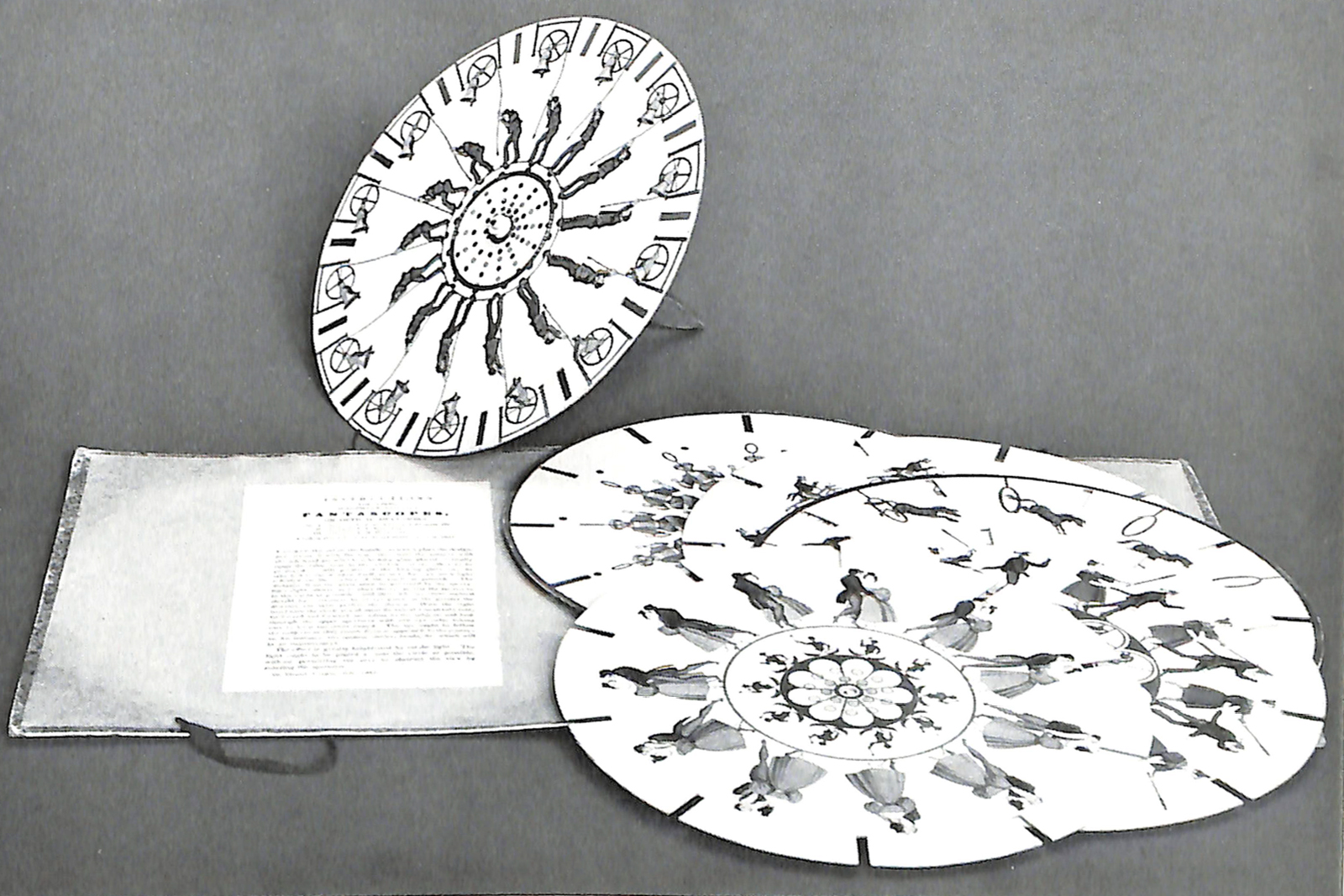

Fig. 4. Fantascope, By T.T. Bury. 2nd series. London, July 1833, Published by Ackermann & Co. 96 Strand. Part of the Yale Center for British Art Collection.

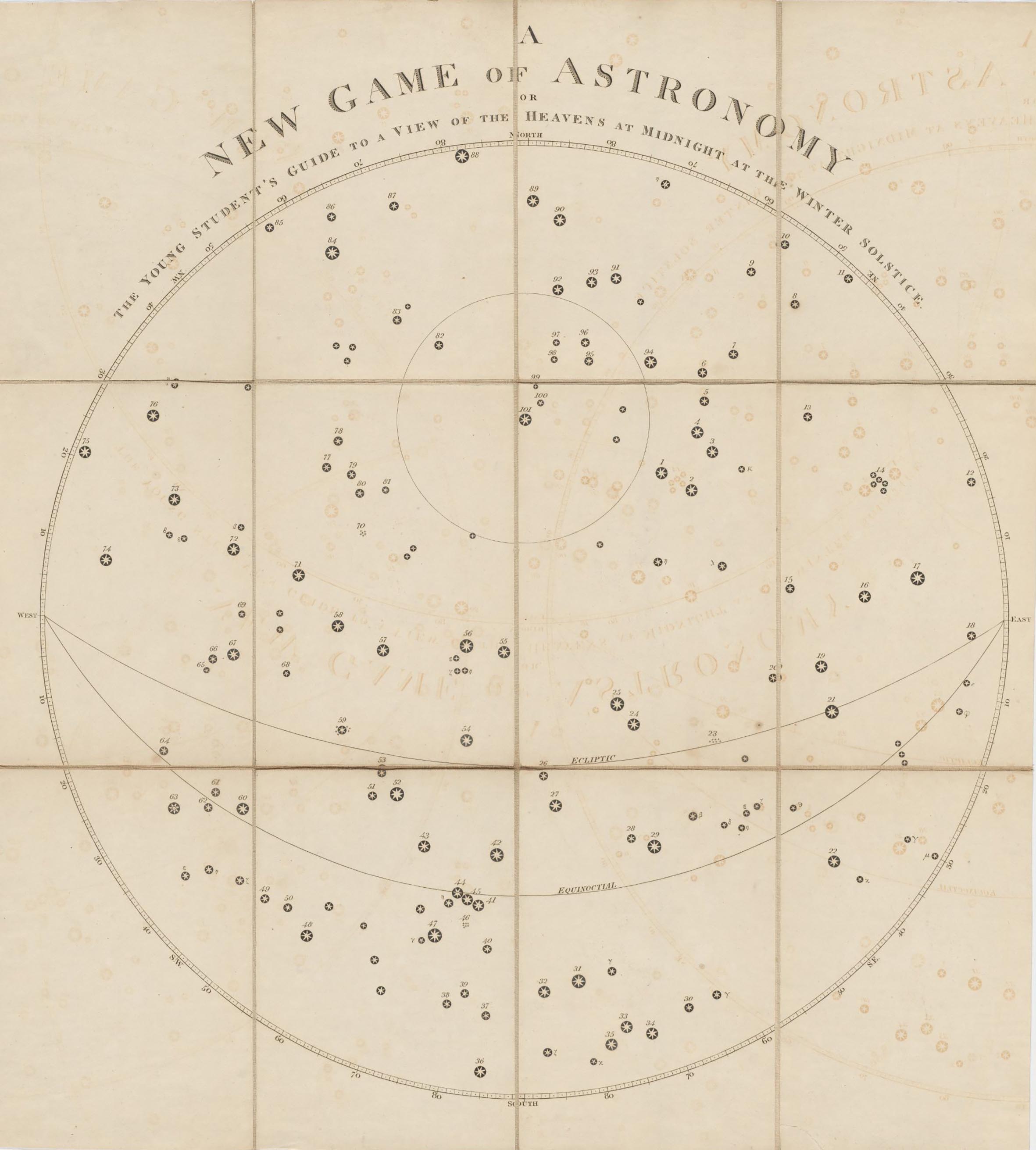

Fig. 5. The study of the heavens at midnight during the winter solstice, arranged as a game of astronomy. London, 1814, Designed by Alicia Catherine Mant and published by J. Harris. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

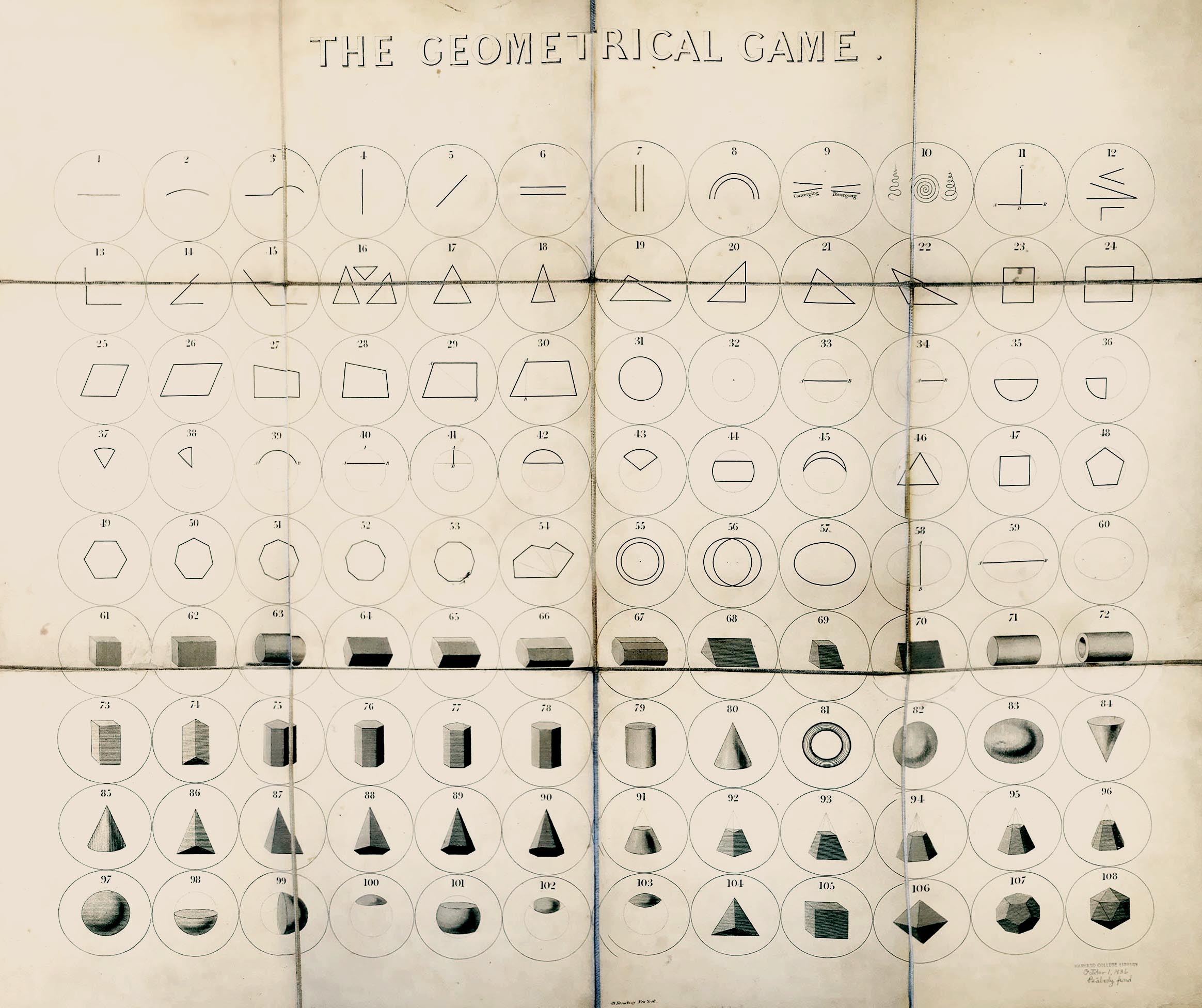

Fig. 6. The Geometrical Game. New York, ca. 1824, Published by Row Lockwood. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Part 3: Bringing the notion from “outside” the home, into it

Fig. 5. The study of the heavens at midnight during the winter solstice, arranged as a game of astronomy. London, 1814, Designed by Alicia Catherine Mant and published by J. Harris. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 6. The Geometrical Game. New York, ca. 1824, Published by Row Lockwood. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Part 3: Bringing the notion from “outside” the home, into it

The simultaneous explosion of popular literature concerning the types and function of scientific instruments at the time closely follows the process by which scientific demonstrators and publishers began to promote new scientific ideas emerging at the time.

Similarly, the emergence of new conceptions of, as well as the nature of the relationship between objectivity and subjectivity led to both new methods and techniques in the actual practices of science, and at the same time, influenced new ways of organizing the household economy. The rise of statistical thinking, or the avalanche of printed numbers as Ian Hacking characterizes the changes in statistical history at the first half of the 19th century, had as its aim the ambition not only to quantify but also to modify the world in which we live. Statistics aimed to perfect productivity, the living and working conditions of society, and to control the character or moral sense of the population. Domestic games, as a place where people formed ideas of themselves, had a similar role in reinforcing a larger set of assumptions about how the designed environment might act as a means to address new psychological ideas at the time which emphasized the malleability (and therefore improvability) of man.

Perhaps more interesting is that these ideas were also manifested in the design of contemporary toys and board games. To take a case point, Fantascope, published in London in 1833 by Ackerman & Co., was a science-inspired optics toy that was very popular throughout the 19th century. In fact, Fantascope was a phenakistoscope, or what was the first widespread animation device. Fantascope works by creating the illusion of motion and came in the form of 6 interchangeable spinning cardboard disks, each of which could be attached vertically to a wooden and ivory handle. According to Brewer, “[t]he phenakistoscope works because the eye retains an image for a split second after seeing it. Thus, images shown in rapid succession seem to merge […].” The “scientific curiosity” inspired by the optical effect produced by this toy is emblematic of the attempt to popularize scientific thinking to the broader culture at large.

Conclusion

In this paper I have tried to show that the history of domesticity, cartography, and the development of new scientific instruments are interconnected. This interconnection can clearly be seen, I have argued, in the emergence of board games in the 18th century. Not only is this the case by the mere spatio-temporal coincidence of domesticity, cartography, scientific instruments, and this new genre of domestic entertainment, but more importantly, insofar as board games functioned as an instrument for the construction of a new form of subjectivity grounded in the various transformations in the types of knowledge, education, and citizenship required for this new collective project of modernizing the world.

But while both maps and board games share an ambition for the process of abstraction, there are also clear differences at the level of the innerworldly experience each affords.

With respect to board games, and toys in general, there is a dimension of attempting to recreate or simulate through a kind of microcosm the lifeworld of the adult by exposing players to the kinds of information required of adults. Maps, on the other hand, have an openness about them insofar as they do much less to constrain the actions of their users, focussing instead on providing accurate information about the conditions of a place (sometimes in purely geometrical fashion, and others with more historical and symbolic context) in order to allow users to make their own plans according to what the place mapped might permit. Given all this, then, perhaps it could be said that the concurrent manifestation of these ideas about childhood, domestic education, and scientifically-informed citizens which came to prominence in the context of 18th and 19th century modernity reveals how some of these desires and the conceptual frameworks within which they thrive are still present with us today in contemporary culture.

1. This research was based on the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University. The collection includes nine playing card games and sixteen board games from 1777-1905 originating from England, France, Germany, and the United States. For the purposes of this paper, only five of them were used. In addition, this paper includes five board games housed at the Yale Center for British Art collection

2. Ariès, P., and Duby, G. (eds). A History of Private Life. Vol. 4: 99-166

3. A new geographical game exhibiting a complete tour through Scotland and the Western Isles. Published in London in 1792 by J. Wallis and E. Newbery. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

4. Bowles’s geographical game of Europe. [London]Published by Bowles and Carver (ca. 1800). Designed by Dr. Nugent. Part of the collection of Board games and playing cards, 1777-1905, of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

5. Lamb, S. Bringing Travel Home to England: Tourism, Gender, and Imaginative Literature in the Eighteenth Century. University of Delaware Press, 2009.

6. Hacking, Ian. “Biopower and the Avalanche of Printed Numbers.” Humanities in Society 5, no. 3–4 (1982): 281

7. Fantascope by T.T. Bury. 2nd series. London, Published by Ackermann & Co. 96 Strand., July 1833. Part of the Yale Center for British Art Collection.

8. Brewer, John, John B. Thomas, Paula D. Matthews, Deborah S. Berman, and Yale Center for British Art. The Cottage of Content: Or, Toys, Games, and Amusements of Nineteenth Century England ; Introd. by John Brewer; Catalogue by John B. Thomas, Paula D. Matthews, and Deborah S. Berman. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1977.: 1

9. Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012. pp. 59-61

According to Barthes, it is not so much imitation which is the sign of abdication, as its literalness: the child cannot constitute himself as anything but an owner, a user, never as a creator; he does not invent the world, he utilizes it; gestures are prepared for him without adventure, without surprise, and without joy. He is turned into a little stay-at-home householder who needs not even invent the springs of adult causality; they are furnished for him ready-made: all he has to do is help himself, he is never given anything he must get through from start to finish.

Independent Study by Candidates for Master's

Degrees

Advisor: Antoine Picon

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Degrees

Advisor: Antoine Picon

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Full text available upon request.

©2019

©2019