The fundamental question that is driving this thesis is: what is it that constitutes the nature of children’s toys today? What motives this question, for me, is the fact that today, we live in a world which is very fast paced and full of constantly changing stimuli. This means that there is important scientific and philosophical issue concerning the kinds of skills children need to learntoday in order to be successful adults. This in turn raises the further question of what kind of people (or “subjects” to put in more philosophical terms) and world we are aiming to cultivate today. It is this question — i.e. what kind of world do we wish to live in? — that will determine what kinds of skills people need to develop in order to maintain whatever types of societies we live in.

Hence my interest in games. How can (and do) games play a role in the development of people? In order to answer this question, the first part of the paper is an historical analysis of the development of board games beginning in the 18th century. There are two reasons for including this historical analysis in my thesis. The first is to understanding how the aims of board games, as well as the techniques by which such aims have been (and are) carried out, have changed over time. Thus, part of my aim in this section will be to show that the purpose of board games (in terms of the skills they aim to cultivate) have changed over the course of the last two centuries.

In order to answer this question, the first part of my thesis is a historical analysis of the development of games beginning in the 18th century. In the 18th and 19th centuries, board games were introduced into the home in order to inspire scientific/experimental curiosity in children with the hope that they would grow to become scientists and engineers who would help western industrialization. During the 18th century, the idea of family started to influence the human condition. Family started to create its own sphere within society stabilizing the boundary between public and private life.

This new tendency toward self-reflective consciousness appeared together with the growing interest in the intimacy of private life, both of which found their spatial expression in the design of the separation of spaces within the household, articulated either by new types of rooms or other architectural elements, such as halls, stairs, corridors, etc. At the same time, a new conception of childhood started to gradually gain importance. Until 16th century children were depicted as men on a smaller scale. It was only in the 19th century that family life is centered around around the child. And this was exactly the time when board games enter the house.

Domestic objects for individual comfort and pleasure along with the architectural space contributed to the process of internal subject formation. The idea of subjectivity as an inner space raised a connection between interior space and human interiority.

Firstly, this interiority was expressed in the changes in the building practice, like the new types of distinctions between the rooms and the interior spaces in general. But except for exploring the spatial parameters of the domestic environment, private life had an undeniable expression in the material contents of home. Furniture, clothes, books, religious objects, toys and games reveal developments over the course of the 18th and 19th century.

Family of 6+1

MARY

MARGRET

MARGE

MAY

MARYANN

MARIA

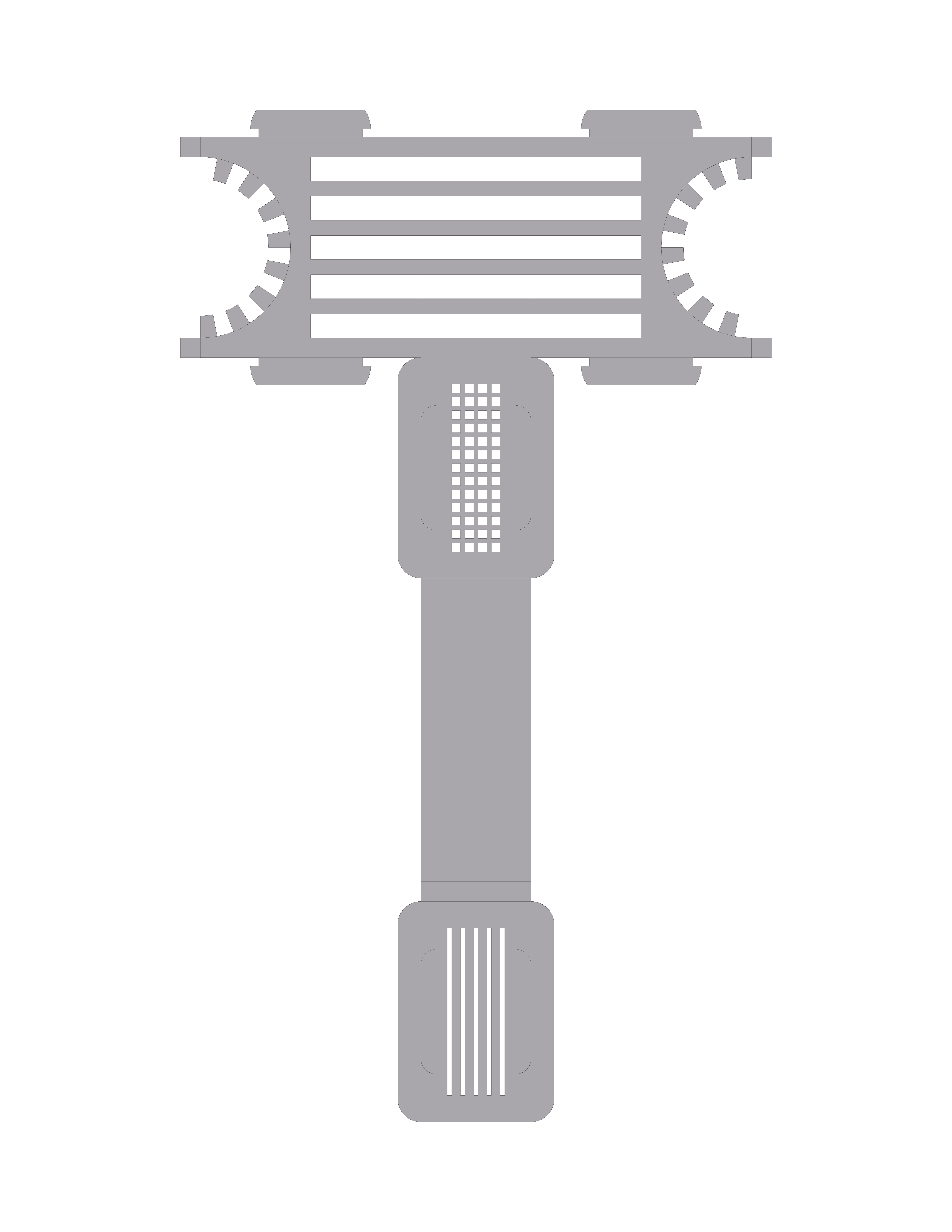

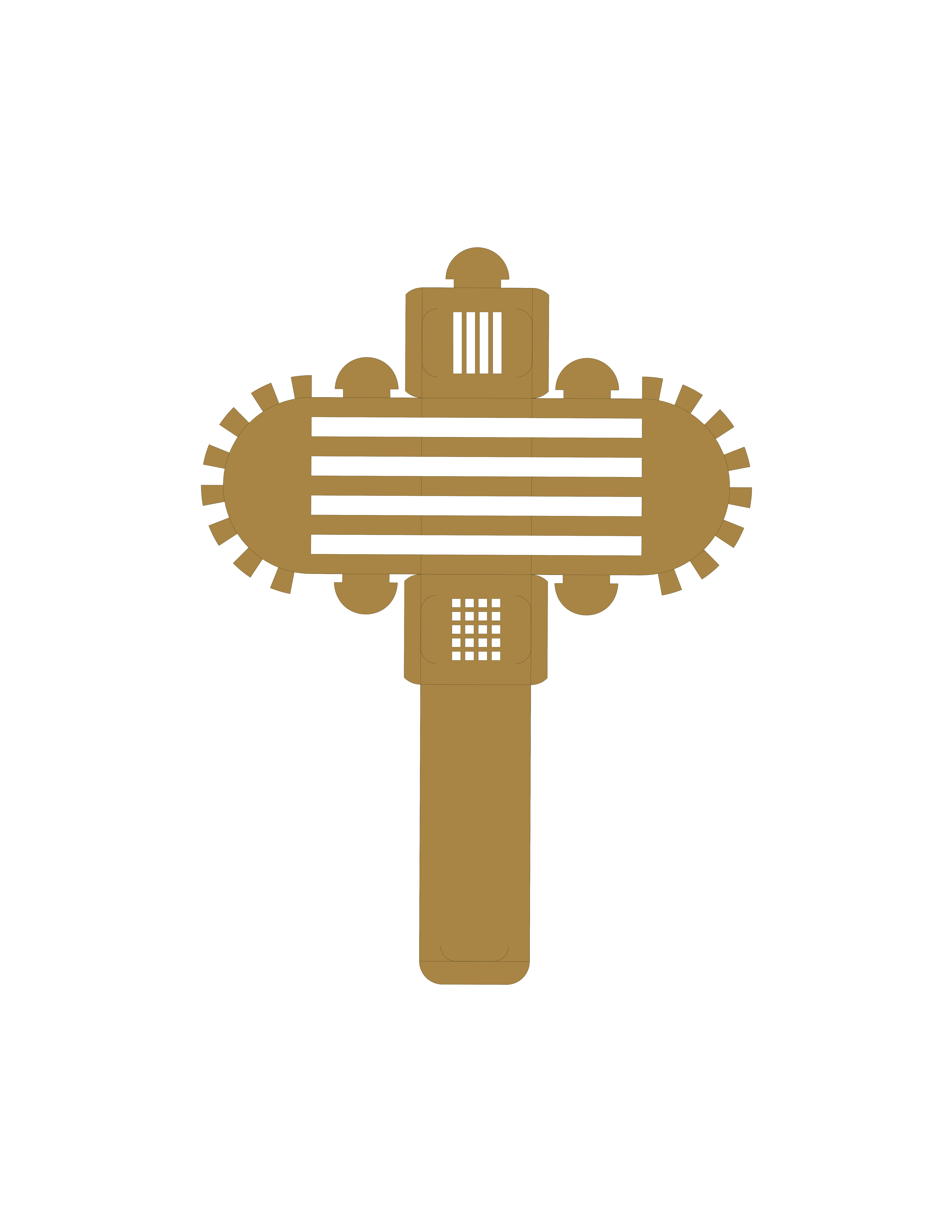

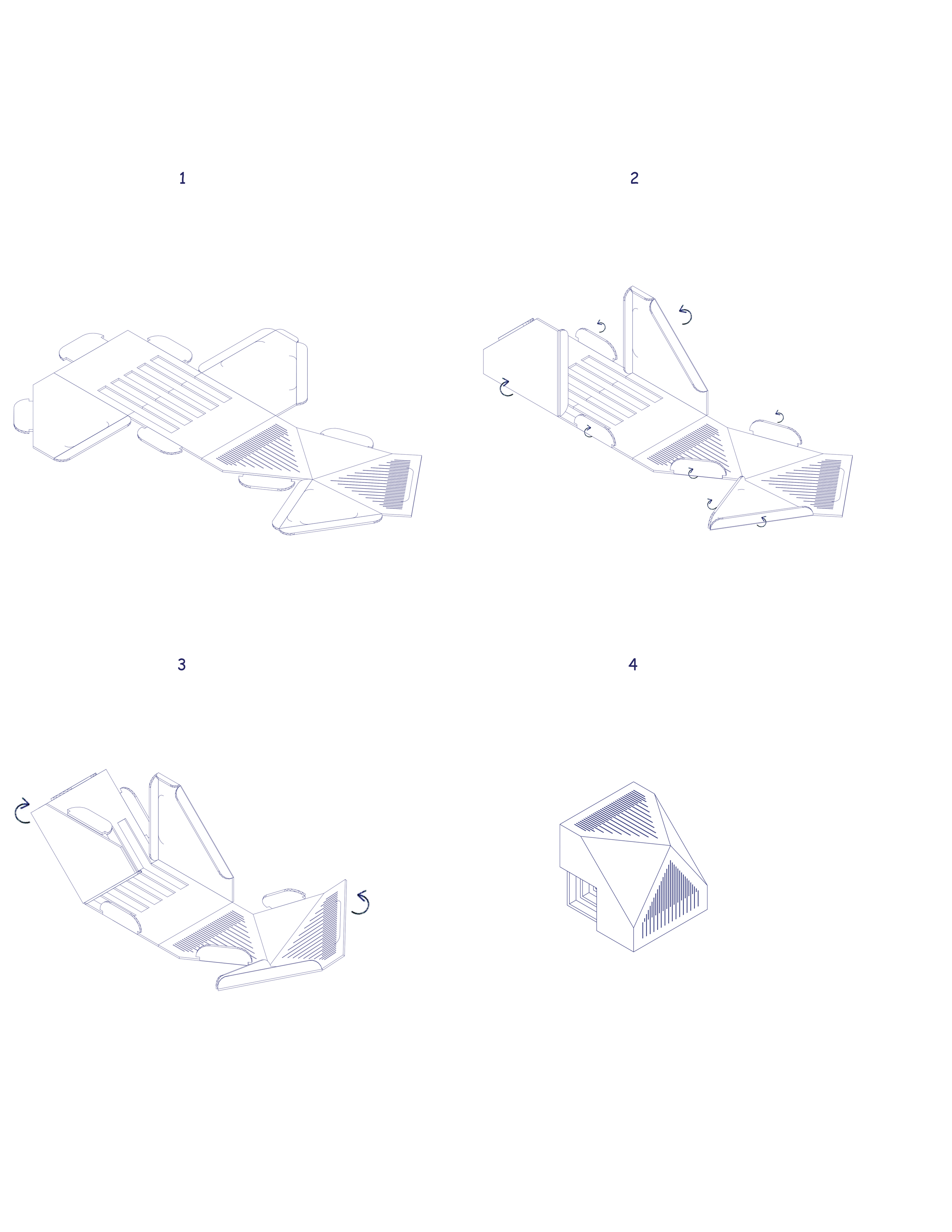

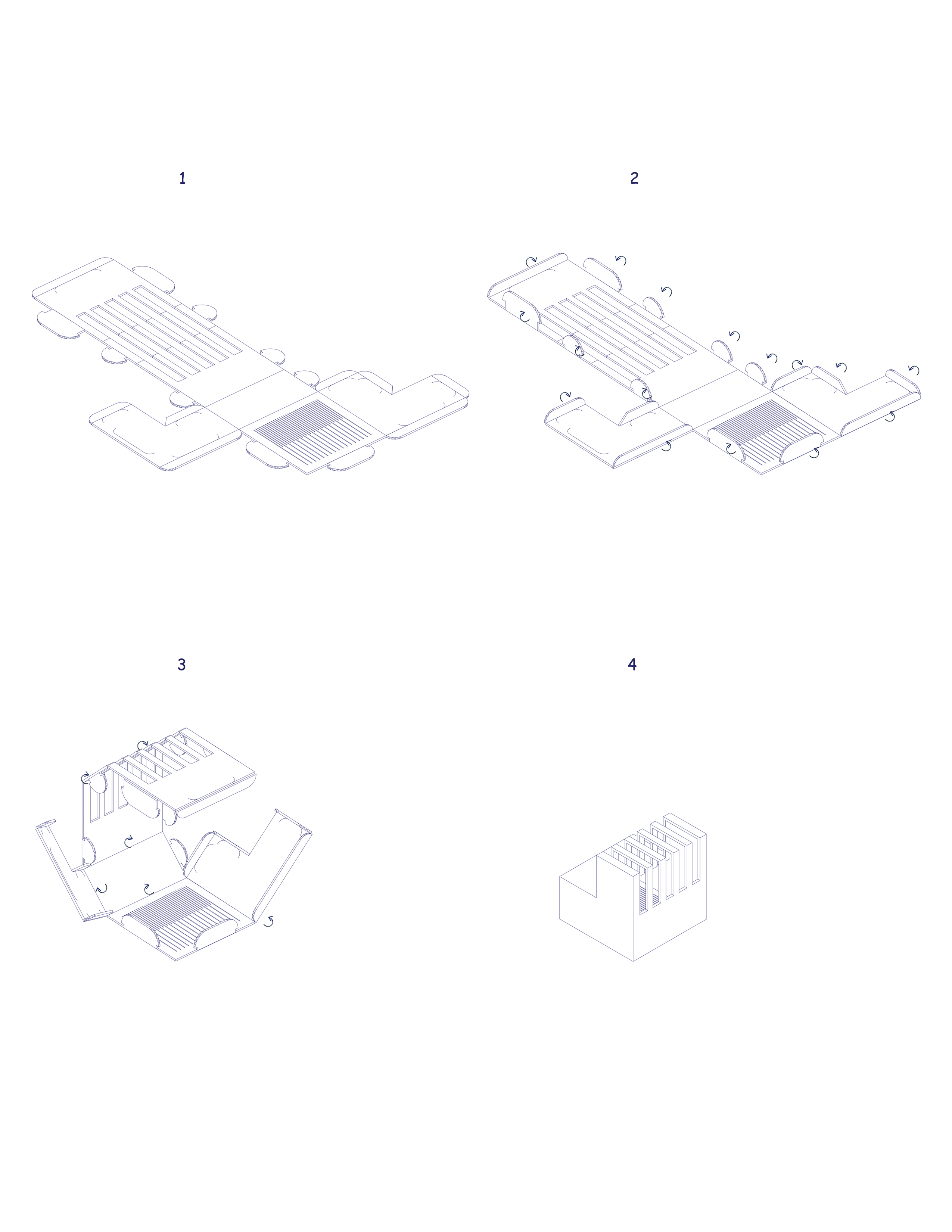

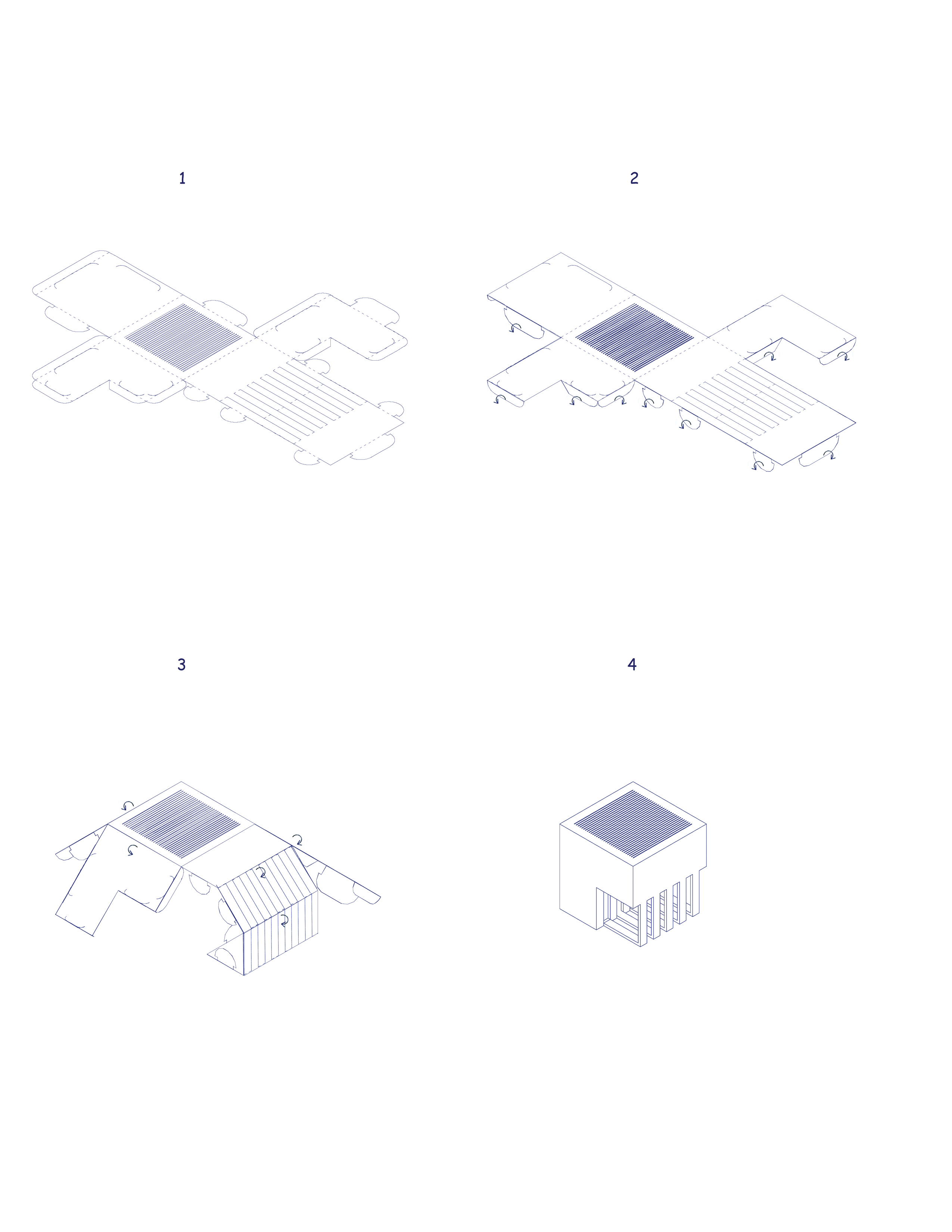

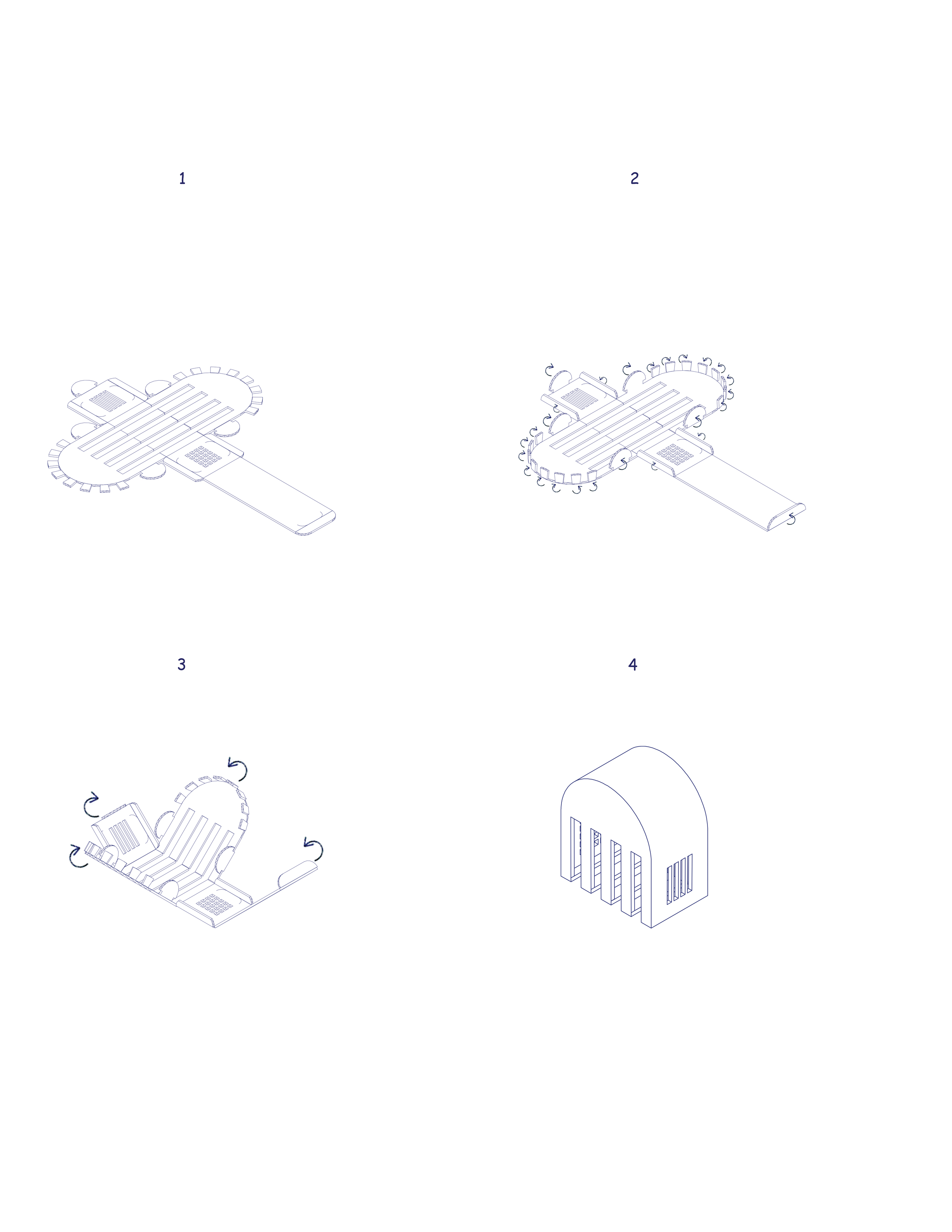

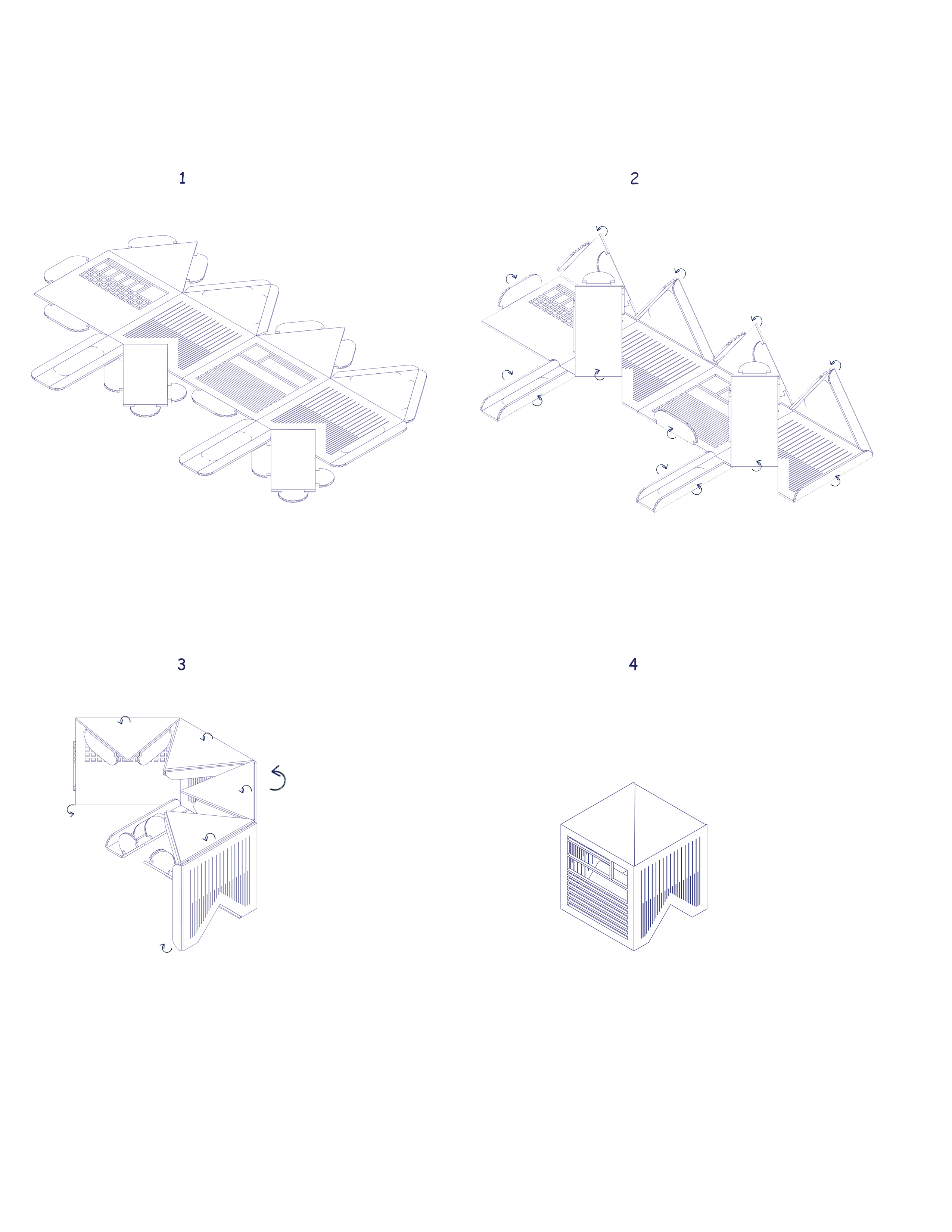

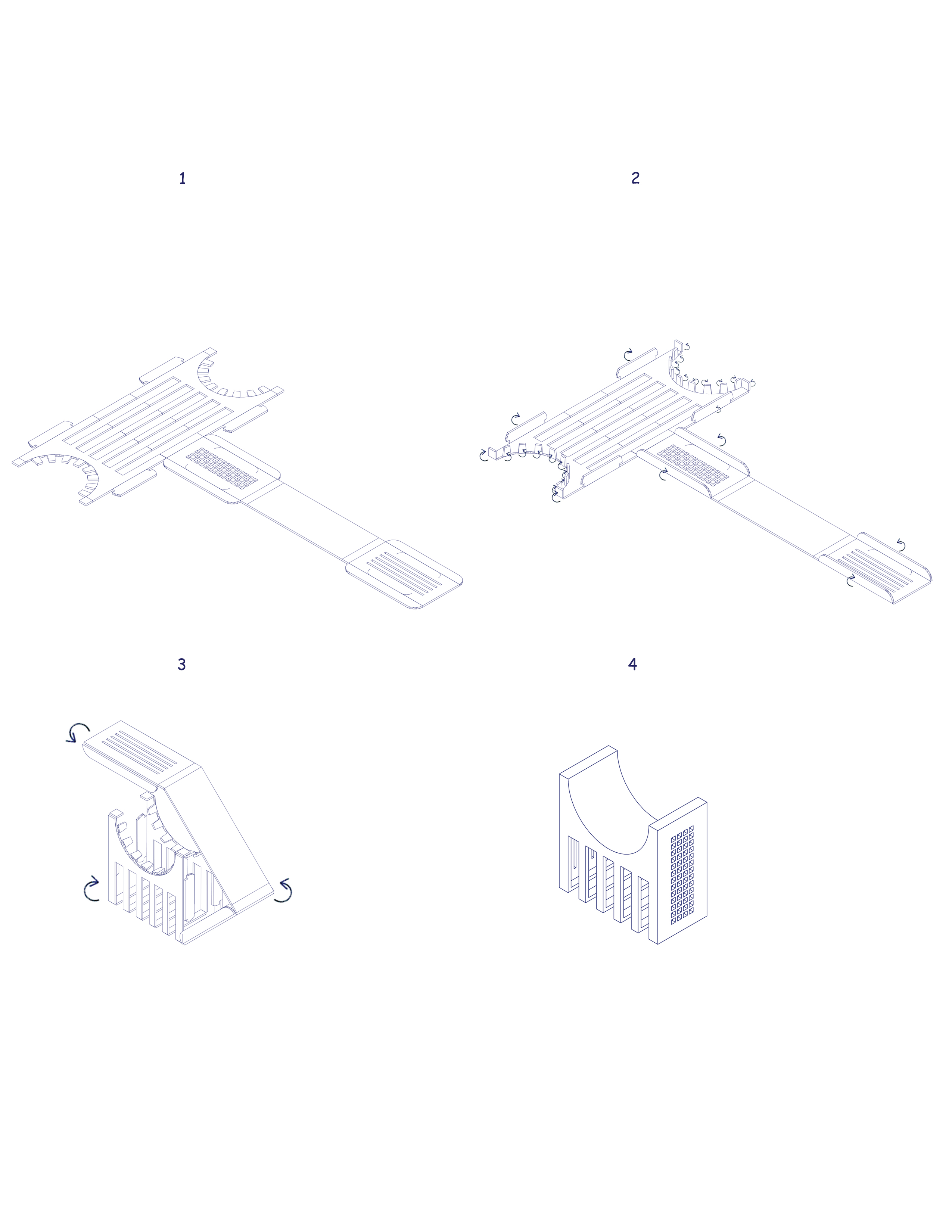

Block Construction Manuals

The new literature about scientific instruments was then brought into the home with the ultimate goal of being the construction of a new type of subject: the individual who participates in the collective endeavor to modernize the world with the conveniences of science, engineering and technology. In 1880, Scientific American devoted a column to an instrument for transmitting and recording images by means of electricity.

The author begins the description of this new technology by stating that: The art of transmitting images by means of electric currents is now in about the same state of advancement that the art of transmitting speech by telephone had attained in 1876, and it remains to be seen whether it will develop as rapidly and successfully as the art of telephony.

This entry reveals the pursuit of objectivity in the 19th century that was inflected by the new scientific practice of making image, had the effect of gradually distributing emerging scientific ideas to popular contexts well beyond the walls of the laboratory.

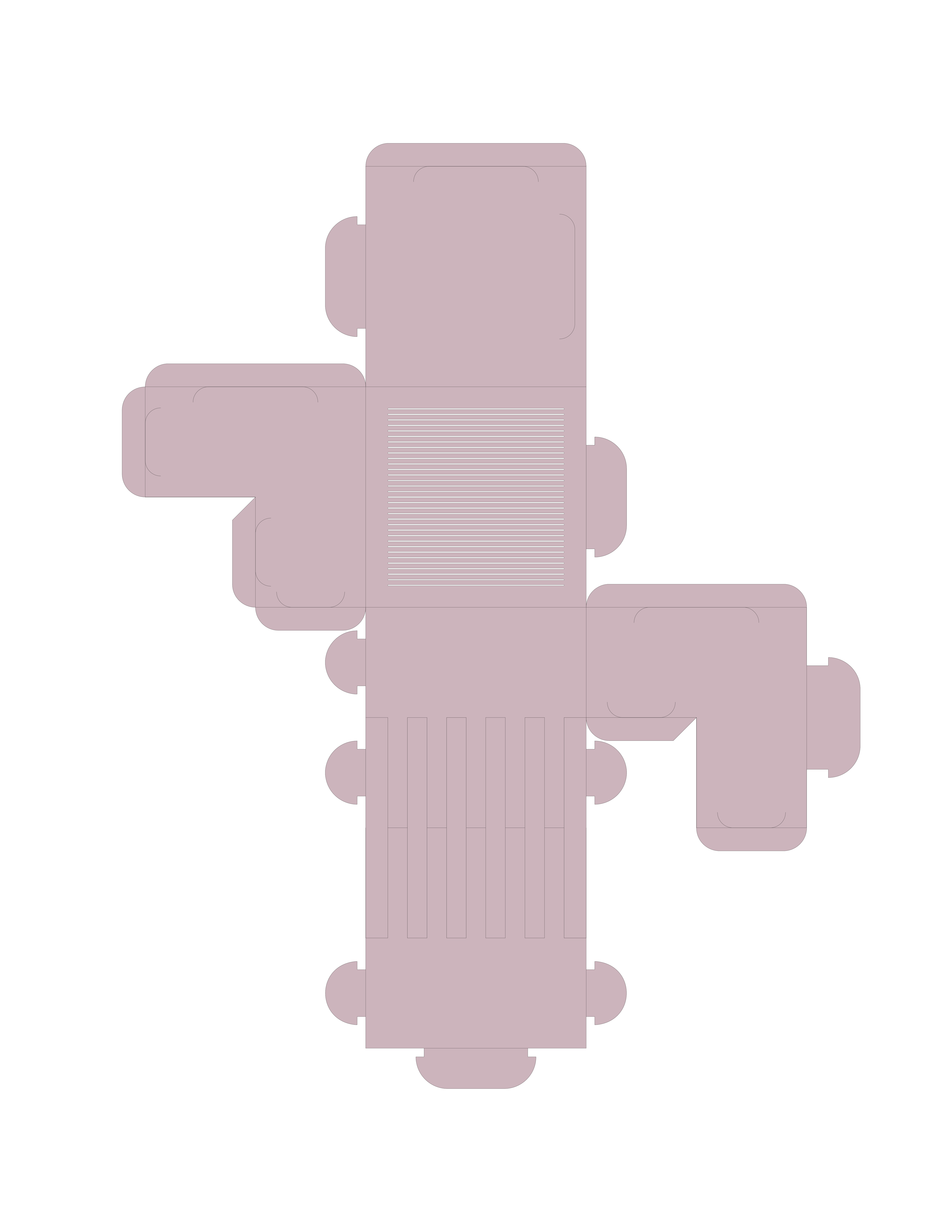

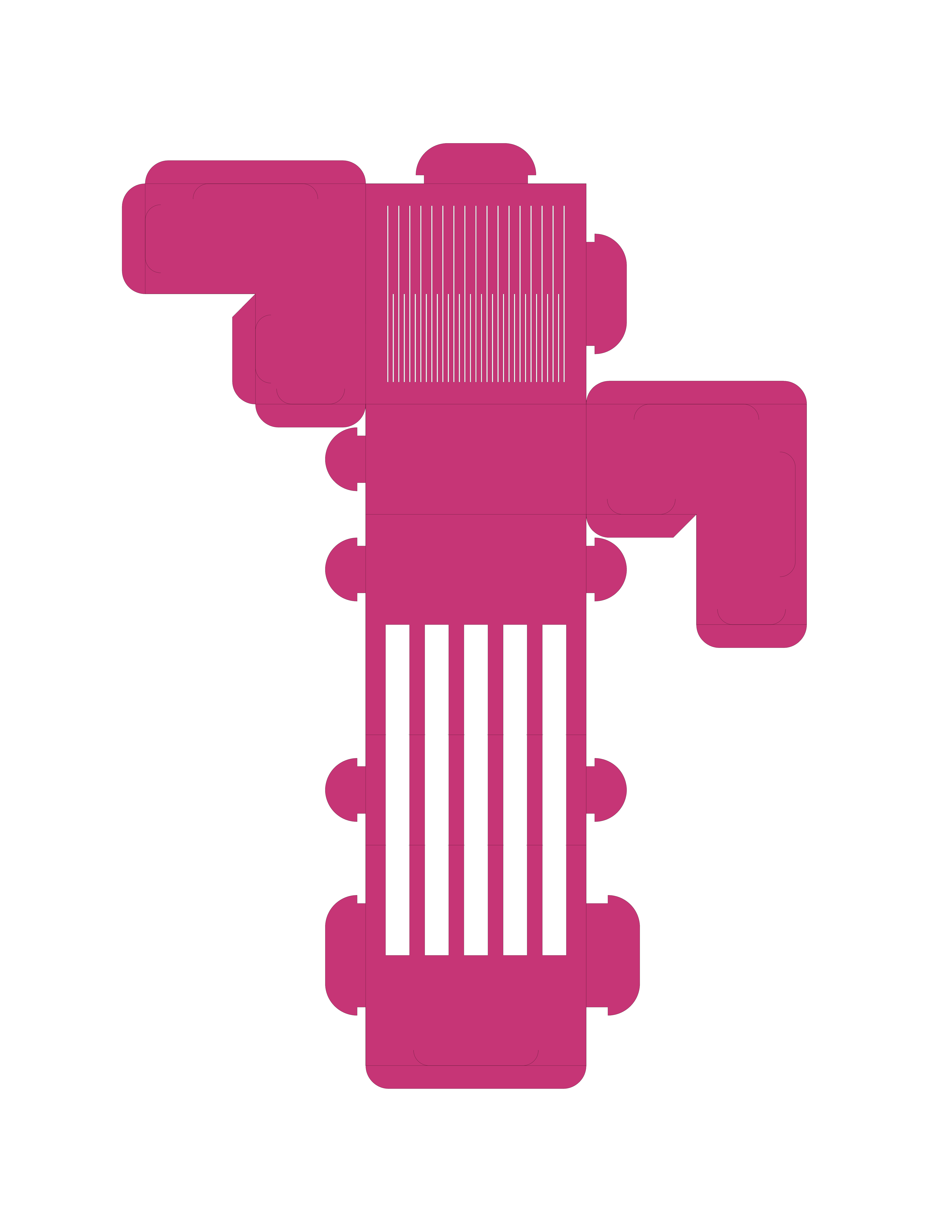

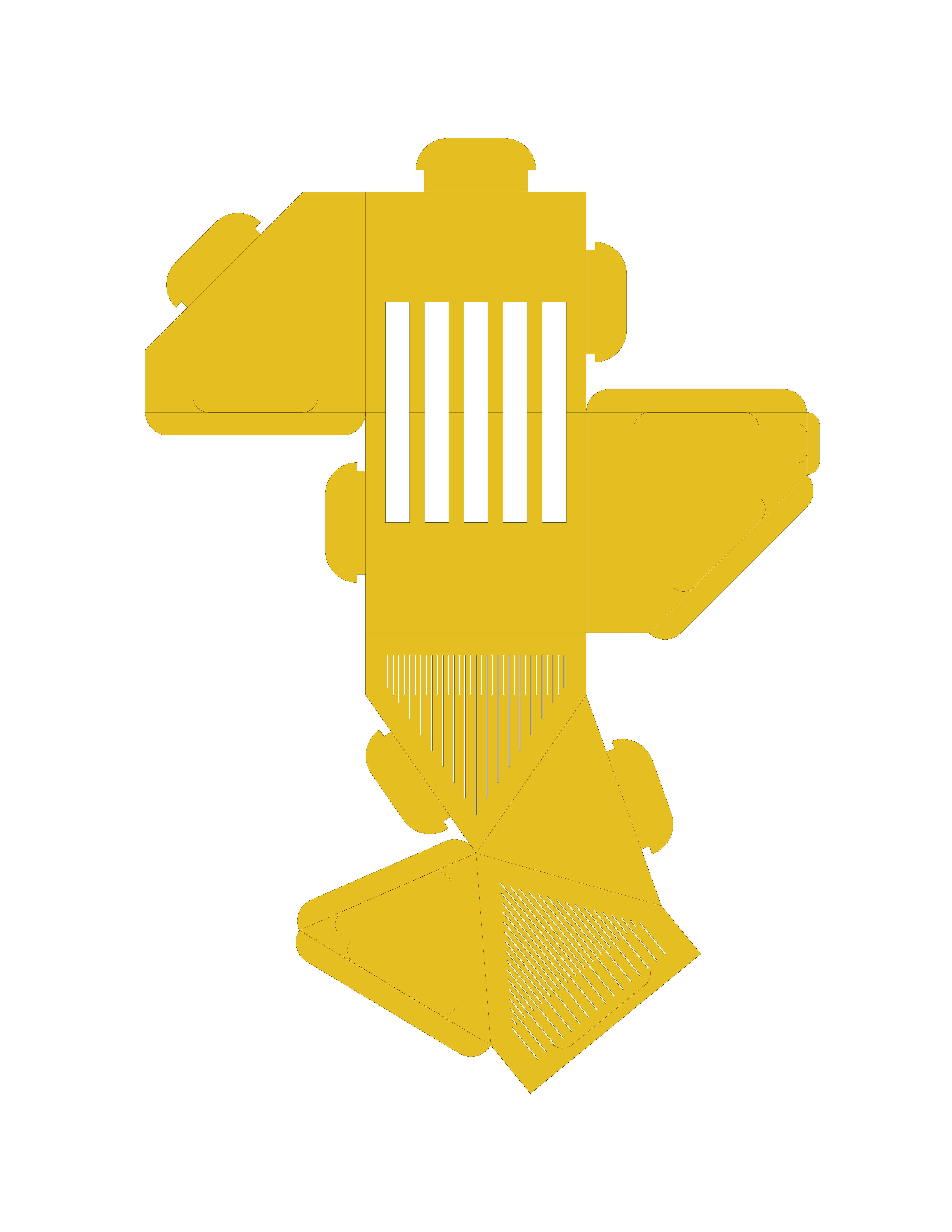

Children’s Drawings

In order to ensure the compatibility between the code and the children’s imagination in the form of the visual output, I asked 15 children, between the ages of 4 and 6, to draw the following shapes: a square, a triangle, a circle, a car, a house, and themselves (see Fig. 18-30). Through observation of reappearing shapes and patterns in their drawings, the next step was the design of the 6 building blocks. Each block had an association with a primary shape (either a square, a triangle, or a circle) and a unique color, as well as a way to connect these with the 5 remaining blocks. The final step was the playtesting of the toy at Botanic Gardens Children’s Center, Harvard’s preschool by three 5 year-olds (see Fig. 21-34).

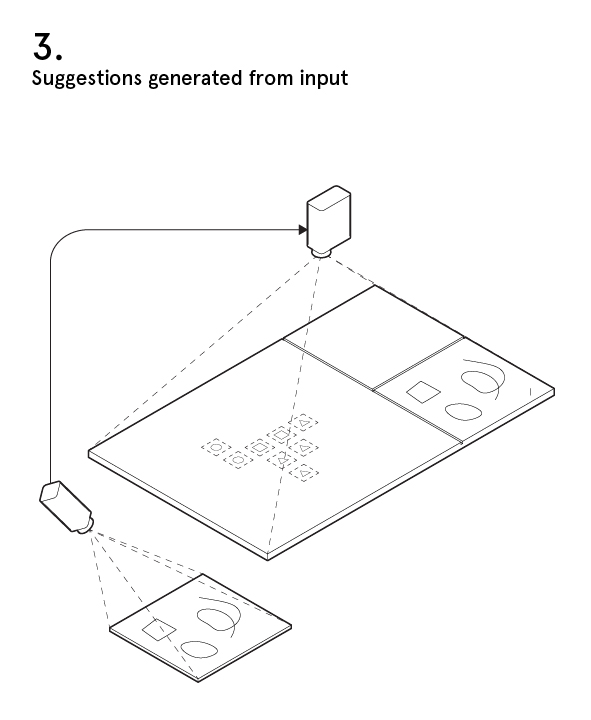

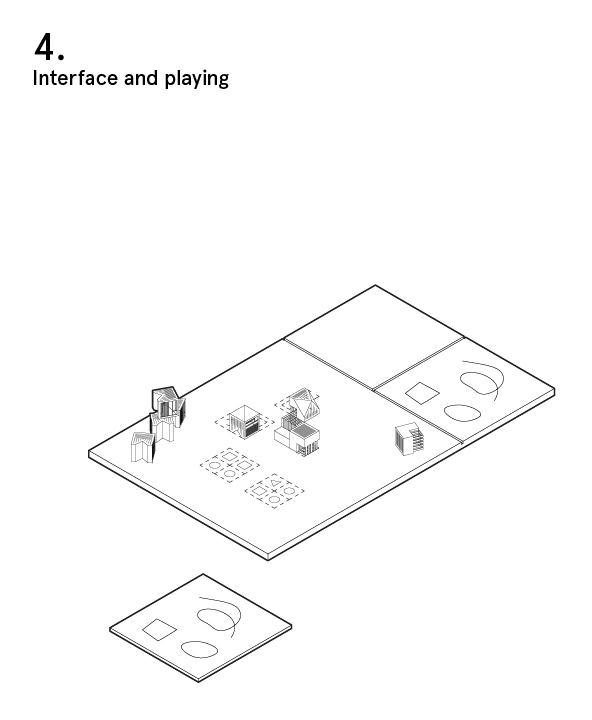

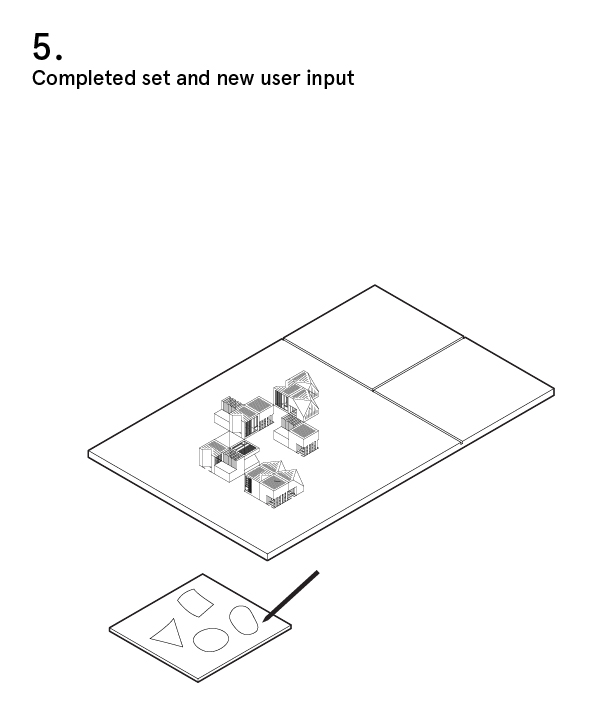

Gameplay

All these entailed the emergence of a new consumerism clearly distinct from the previous period, both in terms of the new aesthetics of colors and material. Also with the introduction of novel objects that entered the household and became commonplace, such as mirrors and clocks, as a response to the simultaneous explosion of scientific instruments.

To do this, I explore the common ground between the conceptions of space prevalent in the toys and board games of the 18th and 19th centuries.

This then leads to my second reason for conducting this historical analysis of boardgames: to provide the necessary historical context for understanding what is distinct about today’s board games as well as what today’s board games can tell us about the types of subjects game designers aim (whether knowingly or not) to cultivate today. This implies that the design of board games is not merely a scientific or technical problem to be solved by the development of a set of techniques or methods by which to effectively facilitate the development of certain kinds of skills in today’s children. But it is also a political and ethical question insofar as, like I have already indicated, the question of what kinds of people and worlds we want to actualize cannot straightforwardly be decided upon by science, technology, or engineering, since such an approach would assume the validity of these ways of thinking for determining the kinds of lives people wish to lead. In order to carry out this historical dimension of my research, I have relied on the collection of board games and playing cards dating from 1777-1905 found in Harvard’s Houghton Library.

Shapes

What’s interesting is that these ideas were also manifested in the design of contemporary toys and board games.

If we accept the actual functional possibilities of such toys went beyond merely educating users about the laws of nature or the axioms of physics (at least as they were understood at the time) by encouraging users to engage in the practice of creative experimentation themselves, then it can be said that the producers of such toys were seeking the roots of subjectivity in the creative powers of the human imagination.

After all, the idea that combining first-hand experience with the very instruments that produced the scientific and technological innovations of the time with the non-linear temporality of unstructured playtime would seem to be ideal resources for constructing the subject of modernity—a subject characterized by a seemingly innate interest in the production of forms of knowledge effective in carrying out the strategic management of problems of a global scale.