Initially linked to wartime efforts to improve military efficiency, the first massive implementation of intelligence tests in the U.S. were deployed during World War I. These tests were developed as a means of determining the level of literacy among the U.S. military’s recruits. It was then during World War II that the full-blown rush to develop and widely distribute a whole range of different methods for the assessment of human intelligence occurred. The rise of interest in the objectification and quantification of human intelligence coincided with the efforts to establish the absolute unification and systemization of science and technology for the purposes of transforming human populations into more easily manageable societies. Within this general pursuit for a more efficient means of regulating populations, the particular concept of intelligence emerged within a number of scientific domains, as did a whole suite of instruments and techniques necessary for measuring the structures of intelligence. Despite their relative heterogeneity, these scientific discourses all shared the common goal of isolating and documenting the proper functions of the human-mind by rendering them visible to the scientific and medical gaze.

But while there was a more or less shared goal among this diversity of research efforts, the theories attempting to explain the structures of intelligence were not only highly diverse, but often in direct conflict with one another. Τhese theories emerged from different areas within psychology and emphasized the different functional aspects of human cognitive performance and their measure. Primary among the inconsistencies between these theories concerned were the precise number of capacities constitutive of human intelligence as well as the overall, global organization of such capacities.

Theoretical and explanatory frameworks began with approaches such as “Psychometrics” and “Behaviorism”, which eventually led to the emergence of “Cognitive Science” and the study of the brain itself (or what is today commonly known as “Neuroscience”).

Additionally, behind these various theories of intelligence and the techniques developed for its study were a number of incentives driving these attempts to understand intelligence which were not at all based in anything like a “pure desire to know” (as it were) on the part of scientists and researchers. Rather, there was immense pressure and reward from a variety of state and government agencies and institutions, all of which wanted detailed knowledge concerning human intelligence for military, educational, and civil purposes. Alongside state-funded actors, there was also significant interest from corporations and other for-profit private enterprises. This led to the creation of this new scientific field and was ultimately of crucial importance in shaping the trajectory of much of the post-war technological innovation that have occurred over the course of the 20th C. throughout the United States and Western world generally.

The development of these new theoretical languages for understanding, interpreting, and evaluating human intelligence primarily relied on methods of quantification and measure which were heavily influenced by the prominent use of statistics in the ongoing industrial and technological revolution. In other words, the widespread use of statistical methods in other fields of research was transferred into discussions about the nature of the human mind. The sheer intensity of this transfer is illustrated by both the diversity as well as the range of scientists from all over the Western world who were concerned with the scientific study of the human mind.

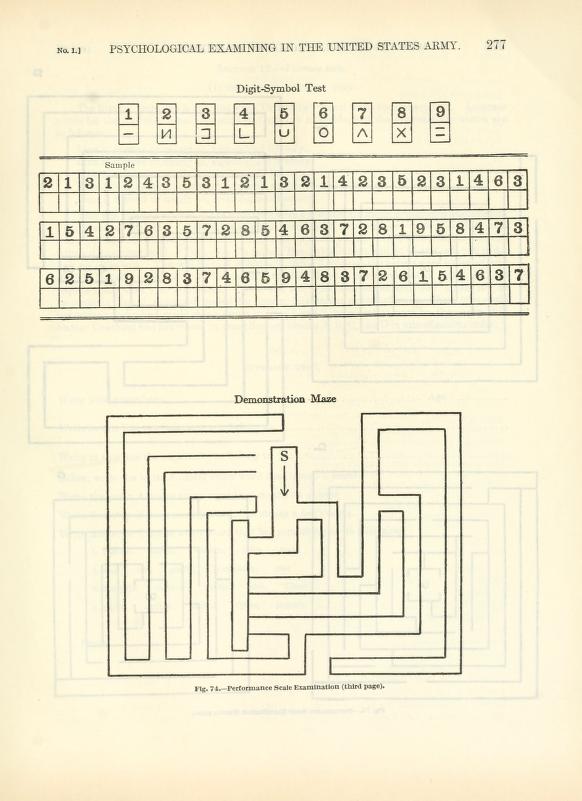

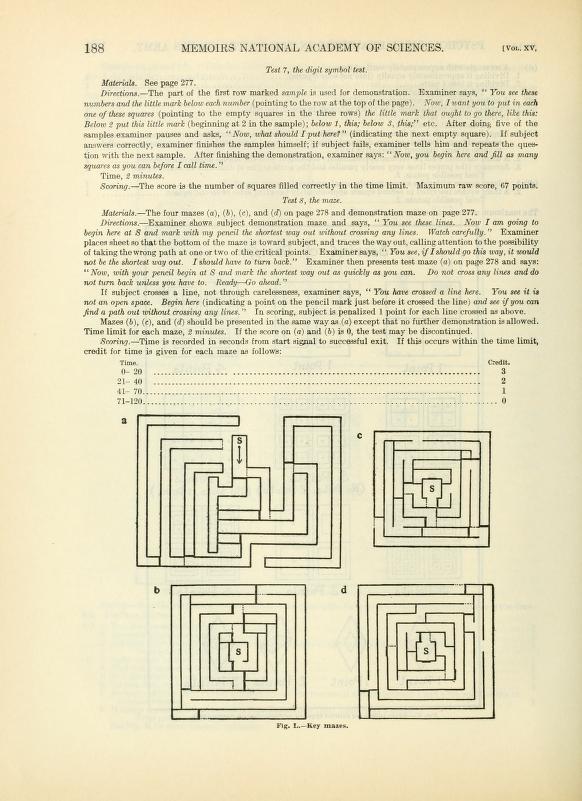

Fig. 1-3. “Psychological Examining in the United States Army : Yerkes, Robert Mearns, 1876-1956 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, [Washington, D.C. Govt. Print. Off.], 1 Jan. 1970.

Additionally, behind these various theories of intelligence and the techniques developed for its study were a number of incentives driving these attempts to understand intelligence which were not at all based in anything like a “pure desire to know” (as it were) on the part of scientists and researchers. Rather, there was immense pressure and reward from a variety of state and government agencies and institutions, all of which wanted detailed knowledge concerning human intelligence for military, educational, and civil purposes. Alongside state-funded actors, there was also significant interest from corporations and other for-profit private enterprises. This led to the creation of this new scientific field and was ultimately of crucial importance in shaping the trajectory of much of the post-war technological innovation that have occurred over the course of the 20th C. throughout the United States and Western world generally.

Additionally, behind these various theories of intelligence and the techniques developed for its study were a number of incentives driving these attempts to understand intelligence which were not at all based in anything like a “pure desire to know” (as it were) on the part of scientists and researchers. Rather, there was immense pressure and reward from a variety of state and government agencies and institutions, all of which wanted detailed knowledge concerning human intelligence for military, educational, and civil purposes. Alongside state-funded actors, there was also significant interest from corporations and other for-profit private enterprises. This led to the creation of this new scientific field and was ultimately of crucial importance in shaping the trajectory of much of the post-war technological innovation that have occurred over the course of the 20th C. throughout the United States and Western world generally.

The development of these new theoretical languages for understanding, interpreting, and evaluating human intelligence primarily relied on methods of quantification and measure which were heavily influenced by the prominent use of statistics in the ongoing industrial and technological revolution. In other words, the widespread use of statistical methods in other fields of research was transferred into discussions about the nature of the human mind. The sheer intensity of this transfer is illustrated by both the diversity as well as the range of scientists from all over the Western world who were concerned with the scientific study of the human mind. And yet, it is somewhat ironic, as John Carson points out, that “it was in America, for all its individualism, that mental difference was collapsed down to a single register — intelligence as something unitary — and [was] relied on especially in education and industry to establish a justifiable basis for differentiating the masses.” In other words, it was in the United States that the differences between individual persons would come to be determined on the basis of this singular, unitary principle of intelligence; and as I shall defend in this paper, this principle of intelligence was primarily conceived of as consisting in, and therefore measured by, each individual’s capacities in spatial perception. That is to say, within the discussions concerning human intelligence by both the military and corporate sectors of American society during the mid-20th century, it was the perception of space that was taken to be both the premiere form as well as the most direct measure of intelligence.

Fig 4.

Women in the Relay Assembly Test Room, ca. 1930. Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection

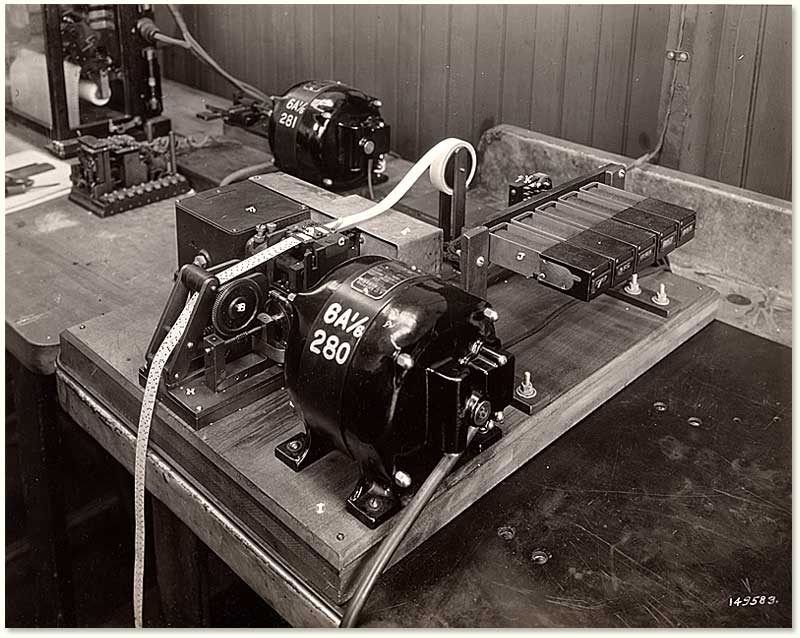

Fig 5. Performance Recording Device. Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection

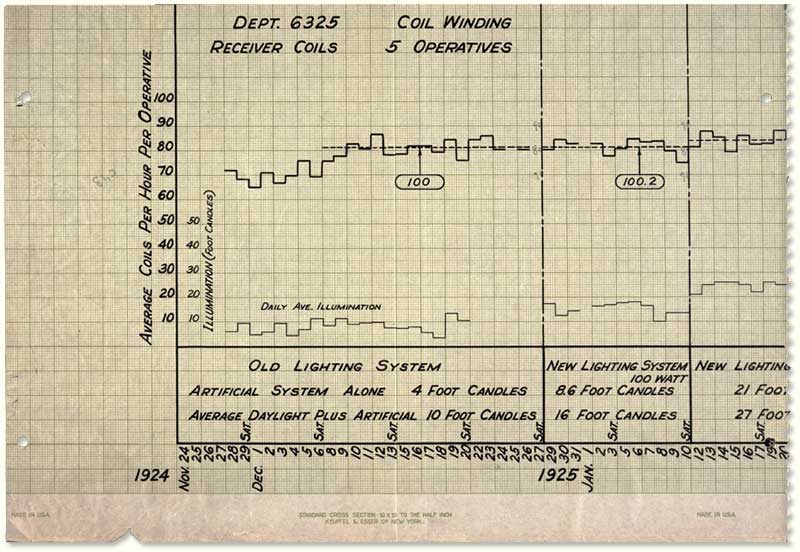

Fig 6. Hourly Output Dept. 6325 Receiver Coils, Illumination Study, 1926. Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection

In addition to the primacy given to spatial intelligence in both the military and private-industrial contexts, these two discursive milieus also shared as their goal the management of individuals within large institutional organizations. However, the specific techniques and immediate goals by which these respective forms of management were implemented underwent a transformation when the concept of cognitive performance and the techniques used for its measurement migrated from the state-led military context to the private corporate and industrial sector of American society. In particular, I focus on the way these studies formulated the relationship between humans and their environment, which can be seen both in the quest to identify and rank the so-called “spatial abilities” of military recruits but also in the attempts within private industry to incorporate this knowledge about the relationship between environmental factors and the socio-psychological aspects of human behavior in order to more efficiently manage worker productivity and thereby maximize the overall productive output of a given institution.

1. Carson, John. The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. p. 144

2. Ibid. p. 6

Fig 5. Performance Recording Device. Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection

Fig 6. Hourly Output Dept. 6325 Receiver Coils, Illumination Study, 1926. Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection

In addition to the primacy given to spatial intelligence in both the military and private-industrial contexts, these two discursive milieus also shared as their goal the management of individuals within large institutional organizations. However, the specific techniques and immediate goals by which these respective forms of management were implemented underwent a transformation when the concept of cognitive performance and the techniques used for its measurement migrated from the state-led military context to the private corporate and industrial sector of American society. In particular, I focus on the way these studies formulated the relationship between humans and their environment, which can be seen both in the quest to identify and rank the so-called “spatial abilities” of military recruits but also in the attempts within private industry to incorporate this knowledge about the relationship between environmental factors and the socio-psychological aspects of human behavior in order to more efficiently manage worker productivity and thereby maximize the overall productive output of a given institution.

Taking this as my starting point, in the first section of this paper I investigate the development of the concept of human intelligence along with the tools and methods used for its study developed by the U.S. military during the early-20th century. My argument in this section is twofold. First, I demonstrate that the primary reason for the U.S. Army’s initial interest in the study and measure of human intelligence was to find “the right man for the right job”, as it were. This required an objective basis by which each individual could ranked and classified, which ultimately led to the development of the U.S. Army’s “Alpha” and “Beta” intelligence tests during World War I. Following from this, the second part of my argument is that the primary capacity by which the intelligence of recruits would be measured was that of their cognitive spatial abilities. I conclude this section by demonstrating that the development of this idea of so-called “spatial intelligence” was to have a lasting impact on the popular understanding of human intelligence which remains with us even today.

Following from this, in the second section of this paper, I attempt to show that a subtle conceptual migration took place in the function and style of managing individuals when the measurement of human intelligence — and spatial intelligence in particular — was imported from its initial military context for use in the private business sector of America during the 1920s. Here I argue that if the motivational force driving the military’s interest in the use of intelligence testing was to ensure that each position within its hierarchy was occupied only by those individuals whose cognitive abilities allowed them to effectively fulfill the duties proper to given role, then once the use of intelligence testing found its way into other dimensions of society, the telos of such testing would undergo a shift. That is, once the testing and measurement of human intelligence was imported into the context of private industry, the aim of such testing and measurement became that of maximizing the productivity of each individual — and consequently the overall out of — a given organization.

To show how this happened, I show the Hawthorne Experiments function as a veritable stepping stone by which this subtle shift in the use of human intelligence testing took place. My basic contention here is that the Hawthorne Experiments not only opened the door for the emergence of fields such as Industrial Psychology and Human Factors, but also that they led to the activation of research programs concerned with how varying qualities and spatial distribution of light in a given work environment influences worker productivity. A key part of my argument here is that attempts to quantify human intelligence through the use of scientific instruments were not only a product of the shift from the theoretical framework of Behaviorism (which had dominated psychological science during the 1940s and 50s), but that these attempts to quantify human intelligence were also motivated by their potential use-value to private-interest groups, corporations, and for-profit industry in general.

1. Carson, John. The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. p. 144

2. Ibid. p. 6

HISTSCI 299: Science, State, Corporation

Instructors: Peter Galison and Noah Feldman

Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Instructors: Peter Galison and Noah Feldman

Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Full text available upon request.

©2019

©2019